The Know-Nothing Party Opposed Immigration to America

Of all the American political parties in the 19th century, perhaps none generated more controversy than the Know-Nothing Party, or the Know-Nothings. Officially known as the American Party, it actually emerged from secret societies opposed to immigrants coming to America.

Its shadowy beginnings, and popular nickname, led to it going down in history as something of a joke.

Yet in their own time, the Know-Nothings made their presence known, and no one was laughing.

NATIVISM IN AMERICA

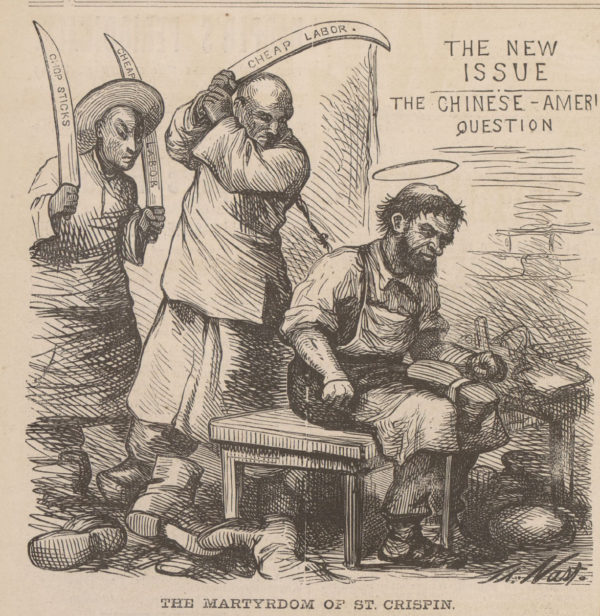

As immigration from Europe increased in the early 1800s, citizens who had been born in the United States began to feel resentment at the new arrivals. Those opposed to immigrants became known as nativists.

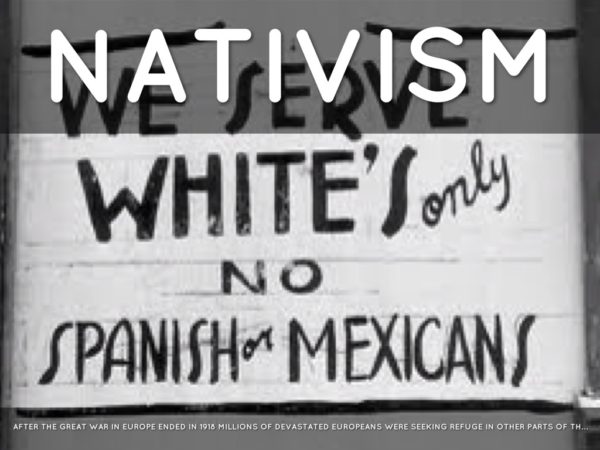

Violent encounters between immigrants and “native-born Americans” would occasionally occur in American cities in the 1830s and early 1840s. In July 1844, riots broke out in the city of Philadelphia. Nativists battled Irish immigrants, and two Catholic churches and a Catholic school were burned by mobs. At least 20 people were killed in the mayhem.

In New York City, Archbishop John Hughes called upon the Irish to defend the original St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Mott Street.

Irish parishioners, rumored to be heavily armed, occupied the churchyard, and the anti-immigrant mobs which had paraded in the city were scared off from attacking the cathedral. No Catholic churches were burned in New York.

The catalyst for this upsurge in the nativist movement was an increase in immigration in the 1840s, especially the great numbers of Irish immigrants who flooded East Coast cities during the years of the Great Famine in the late 1840s.

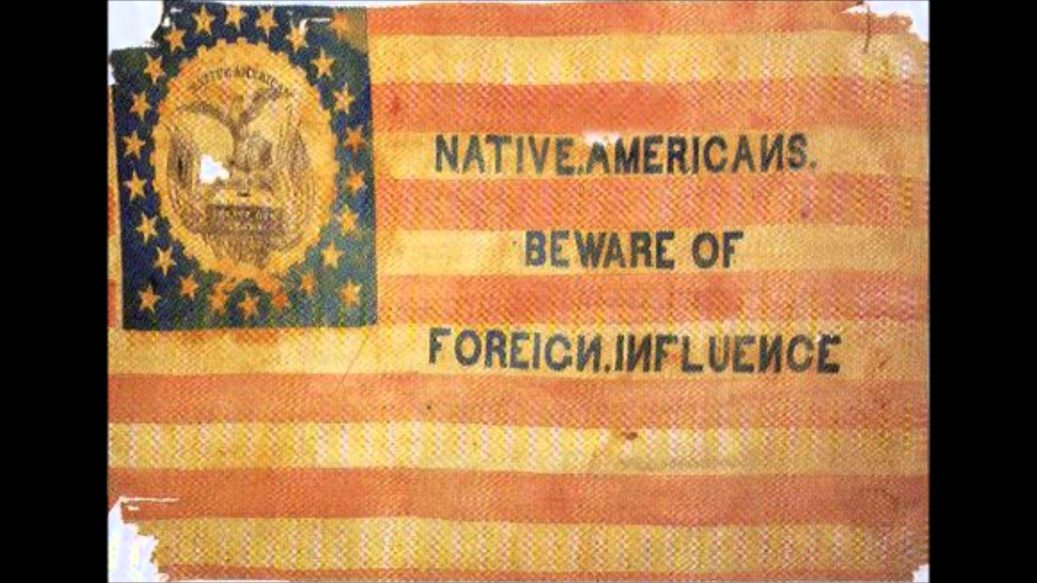

Several small political parties espousing nativist doctrine existed, among them the American Republican Party and the Nativist Party. At the same time, secret societies, such as the Order of United Americans and the Order of the Star-Spangled Banner, sprang up in American cities. Their members were sworn to keep immigrants out of America, or at the least, to keep them out of mainstream society once they arrived.

Members of established political parties were at times baffled by these organizations, as their leaders would not publicly reveal themselves. And members, when asked about the organizations, were instructed to answer, “I know nothing.”

That cryptic answer led to the political party which grew out of the secret societies being commonly called the “Know-Nothings.” The party’s official name was the American Party, and it formed in 1849.

THE KNOW-NOTHING PARTY ATTRACTED FOLLOWERS

The Know-Nothings and their anti-immigrant and anti-Irish fervor became a popular movement for a time. Lithographs sold in the 1850s depict a young man with the caption, “Uncle Sam’s Youngest Son, Citizen Know Nothing.” The Library of Congress, which holds a copy of such a print, describes it by noting the portrait is “representing the nativist ideal of the Know Nothing Party.”

Lincoln noted that if the Know-Nothings ever took power, the Declaration of Independence would have to be amended to say that all men are created equal “except negroes, and foreigners, and Catholics.” Lincoln went on to say he would rather emigrate to Russia, where despotism is out in the open, then live in such an America.

PLATFORM OF THE KNOW-NOTHING PARTY

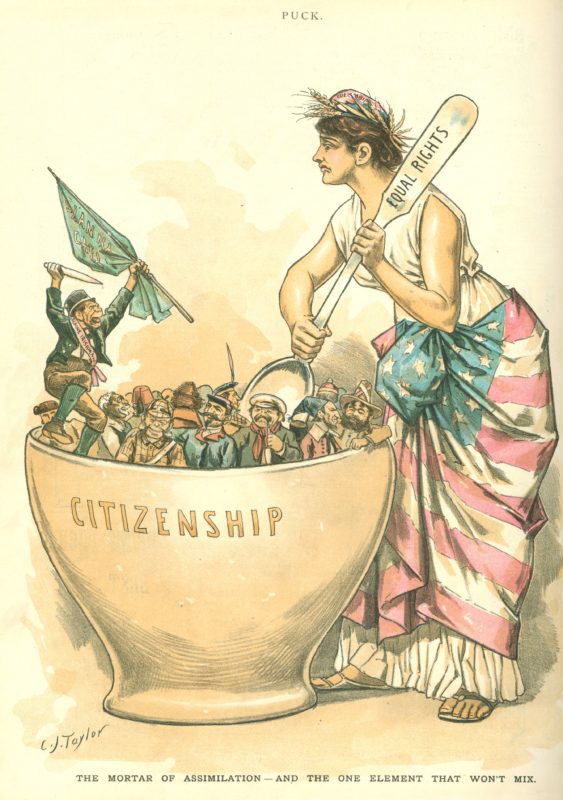

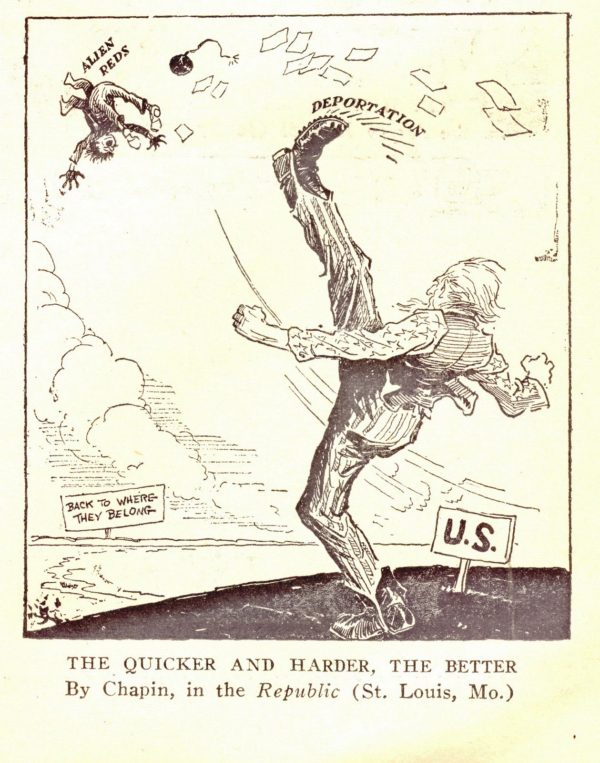

The basic premise of the party was a strong, if not virulent, stand against immigration and immigrants. Know-Nothing candidates had to be born in the United States. And there was also a concerted effort to agitate to change the laws so that only immigrants who had lived in the US for 25 years could become citizens.

Such a lengthy residency requirement for citizenship had a deliberate purpose: it would mean that recent arrivals, especially the Irish Catholics coming to the US in great numbers, would not be able to vote for many years.

PERFORMANCE OF THE KNOW-NOTHING PARTY IN ELECTIONS

The Know-Nothings organized nationally throughout the early 1850s, under the leadership of James W. Barker, a New York City merchant and political leader. They ran candidates for office in 1854, and had some success in local elections in the northeast.

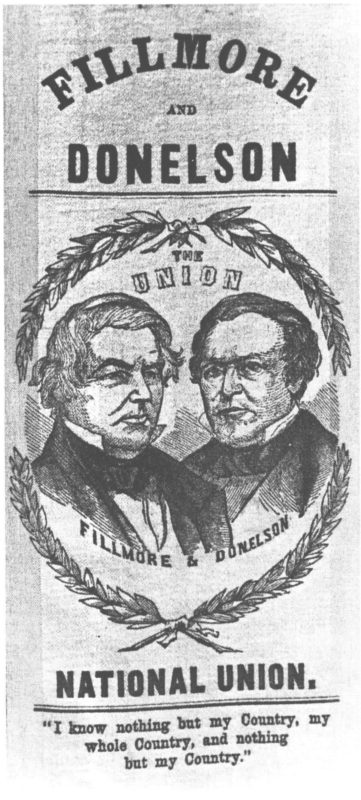

In 1856 former president Millard Fillmore ran as the Know-Nothing candidate for president. The campaign was a disaster.

Fillmore, who had been a Whig, refused to subscribe to the Know-Nothing’s obvious prejudice against Catholics and immigrants. His stumbling campaign ended, not surprisingly, in a crushing defeat (James Buchanan won on the Democratic ticket, beating Fillmore as well as Republican candidate John C. Fremont).

END OF THE KNOW-NOTHING PARTY

In the mid-1850s, the American Party, which had been neutral on the slavery issue, came to align itself with the pro-slavery position. As the power base of Know-Nothings was in the northeast, that proved to be the wrong position to take. The stance on slavery probably hastened the decline of the Know-Nothings.

In New York City, a bare-knuckles boxing champion, Bill Poole, became revered as an enforcer for the Know-Nothing Party. When “Bill the Butcher” died in March 1866 after being shot by a political foe, an estimated 100,000 Know-Nothing sympathizers lined the streets for his funeral procession.

Despite such public shows of support, the party was fracturing, and by 1860 it was essentially a relic. The Know-Nothings joined the list of extinct political parties in America.

According to an 1869 obituary of Know-Nothing leader James W. Barker in the New York Times, Barker had essentially left the party in the late 1850s and threw his support behind Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln in the election of 1860.

LEGACY OF THE KNOW-NOTHING PARTY

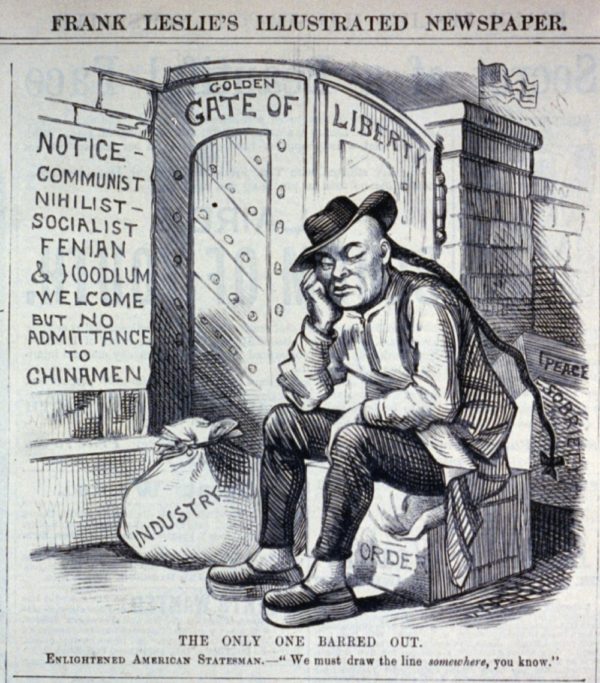

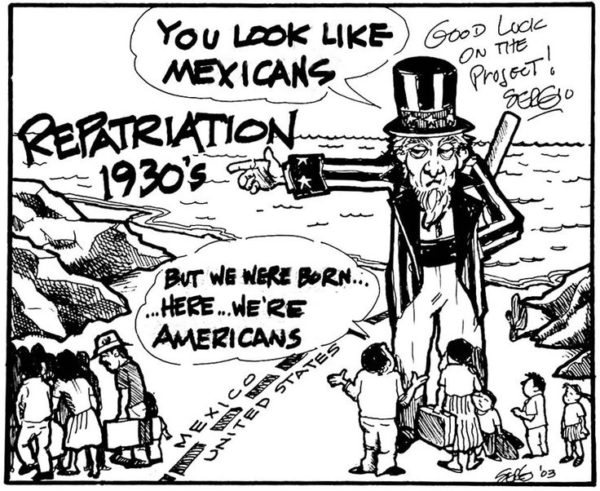

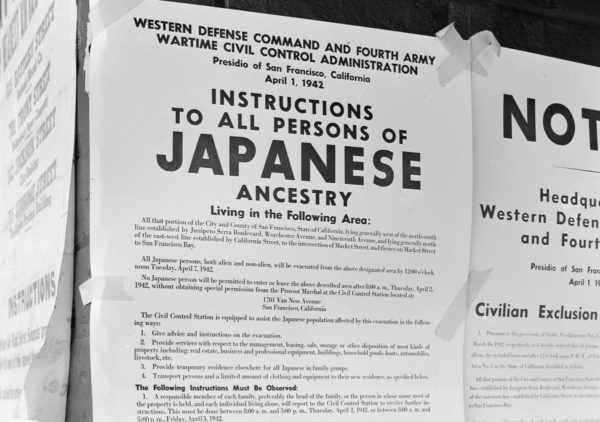

The nativist movement in America did not begin with the Know-Nothings, and it certainly didn’t end with them.

Prejudice against new immigrants continued throughout the 19th century (and, of course, it has never ended completely).