Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was both a man of peace and a man of action. Though is was devoted to non violence, he wasn’t a passivist.

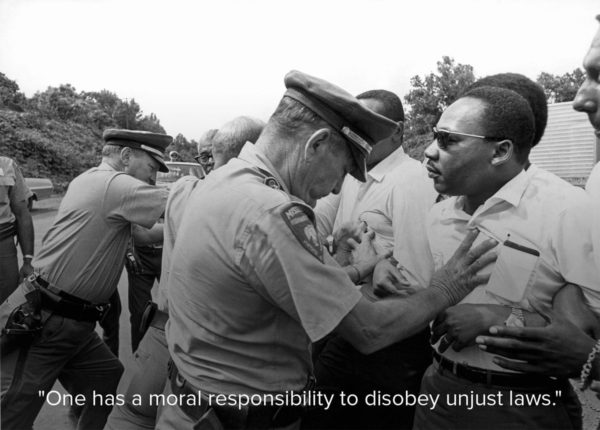

Between 1955 and 1965, King was arrested nearly 30 times. Although he was nonviolent, he resisted oppression and refused to comply with injustice.

Between 1955 and 1965, King was arrested nearly 30 times. Although he was nonviolent, he resisted oppression and refused to comply with injustice.

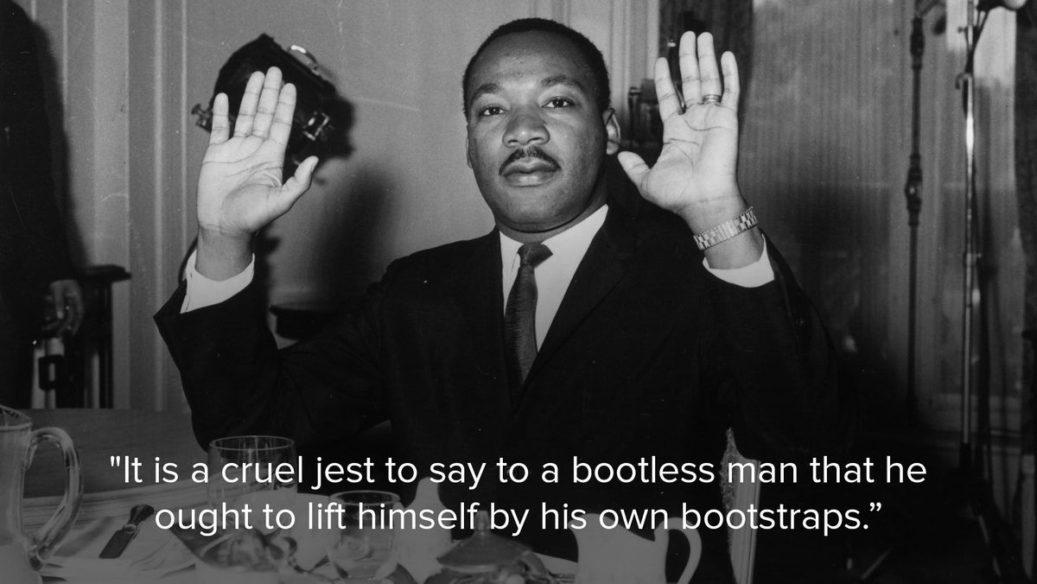

In addition to racial justice, King was a fierce advocate for the rights of the poor. Very aware of the intersection of race and class, he organized the Poor People’s Campaign to fight for economic justice in the United States.

King didn’t accept lazy allyship in the 1960s. He argued that temporary band-aids over wounds of oppression underestimate the depth and magnitude of the institutions that produce them. He advocated that in order to truly help those in need, it’s crucial to understand the systemic causes of poverty, racism and other social inequalities.

King was a firm believer that we all have the capacity to make a difference — regardless of class, age or formal education.

King did not equate nonviolence with no action at all. He demanded freedom with both his words and efforts.

One of King’s most popular quotes is, “I have a dream that … the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.”

But it’s important to note that he also understood it wouldn’t always be possible to change people’s morals. He did believe, however, in the power of legislation for racial justice, and while “the law may not change the hearts of men, it does change the habits of men.”

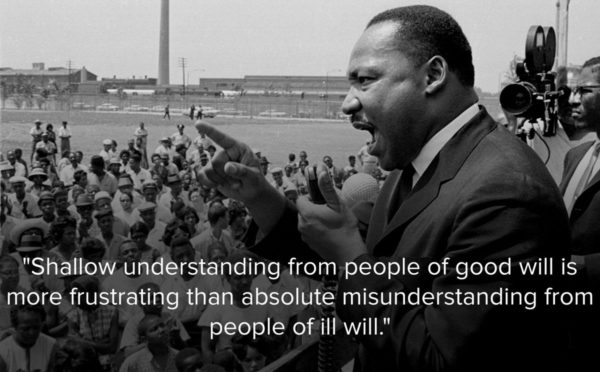

King is frequently framed as a very reasonable leader, often contrasted with the extremism of Malcolm X. However, King was also viewed as an extremist for much of his time as a leader of the Civil Rights Movement. And he embraced it.

In his “Letter From Birmingham Jail,” he explained that being an extremist for a good cause wasn’t something to be a ashamed of. “I gradually gained a measure of satisfaction from the label,” he wrote. “Was not Jesus an extremist for love?”

As a leader of the Civil Rights Movement, King came across many people who accepted some of his beliefs and denied the ones that made them uncomfortable. In his “Letter From Birmingham Jail,” he points toward white moderates who understood his argument for freedom and agreed with his goals, but disagreed with his timing or methods of direct action.

We see the same today, when people only partially quote King or misunderstand his beliefs.

Looking at his words over time, it’s safe to assume King would have wanted a celebration of his life to honor all parts of him — especially the parts that challenge us.